Now I am very aware that this is a very touchy topic. Some people I know seem to think that Appomattox was only a ceasefire. They hang pictures of Lee or Grant on their walls and do homage to their respective sides. In my opinion, both sides had their faults and their favors; but that position was reached only after long, hard hours of meditation. (Not really, but I thought that would sound nice) The positions on the war are evident in the many names for it. You have the Civil War, (which I’ll use) the War Between the States, the War of Northern Aggression, the War of Southern Secession, etc. What I am actually going to do in this post is not talk about the war itself, (I hope y’all covered that in high school) but the situations, debates, and positions taken by people and regions before Fort Sumter was fired on.

Now I am very aware that this is a very touchy topic. Some people I know seem to think that Appomattox was only a ceasefire. They hang pictures of Lee or Grant on their walls and do homage to their respective sides. In my opinion, both sides had their faults and their favors; but that position was reached only after long, hard hours of meditation. (Not really, but I thought that would sound nice) The positions on the war are evident in the many names for it. You have the Civil War, (which I’ll use) the War Between the States, the War of Northern Aggression, the War of Southern Secession, etc. What I am actually going to do in this post is not talk about the war itself, (I hope y’all covered that in high school) but the situations, debates, and positions taken by people and regions before Fort Sumter was fired on.At first, the main controversy between North and South was on the issue of state’s rights. The South believed that states should be able to nullify acts of Congress that were believed to be unconstitutional. It also held that States should be able to secede from the Union, and that the Union was not perpetual. The North (mostly New England and the mid-Atlantic states at this point) did not think that the states had that power. They also held that the Union was perpetual. These issues arose between the two regions as early as 1799, in the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions drafted by those states in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts. It reached open debate on the Senate floor with the Webster-Hayne debates of 1830. These issues continued to grow in power and sentiment along sectional lines until the election of Lincoln in 1860.

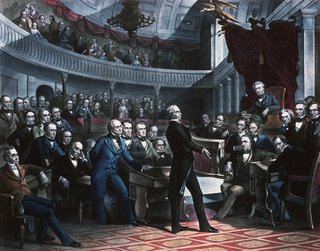

Then, slavery gradually came to the forefront as the distinguishing line between North and South. This issue was held off for many years, starting with the Constitution itself in 1787, extending through the Missouri Compromise of 1820, to when it came to a head in the debates leading up to the Great Compromise of 1850. The origin of this compromise started when California applied for admission into the Union. This time, unlike any other time, there was no slave state to balance the free California. New Mexico, which would probably become a slave state, was not yet ready for statehood. Henry Clay, a Kentucky Senator, attempted to resolve the problem by drafting a compromise. Its final form, drafted by Stephen Douglas, said that California should be admitted into the Union, that New Mexico would be admitted as slave or free when the time came, and that fugitive slaves could be taken from free states by their masters, even after they had run away.

There were great debates all through this time and up to the Civil War with the Kansas-Nebraska Compromise, John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, and other things that aggravated both sides into passionate speech. Most of the debating went on in the Senate, because that was where the two sides were the most equally represented. The main points that both sides insisted on and argued for were the following:

John C. Calhoun of South Carolina stated that the North was aggressing and should grant the South equal rights.

Daniel Webster of Massachusetts said that the South had good cause for complaint against attacks leveled by abolitionists at the region. But he also stated that the North also had good cause for complaint against the South’s aims to expand slavery into other states and across the western frontier. Webster also said that their criticisms against the North for its industrialization were just cause for complaint. However, he declared emphatically, the talk of peaceful secession should cease. There could be no such thing while the sun still rises and sets. Unfortunately, Webster was right.

William Seward, an abolitionist from New York, said that there was a higher law that men were bound to. This law forbade slavery. (And thus, its expansion) This appeal to a higher law became common among abolitionists.

Jefferson Davis, the future president of the Confederacy, stated that the North was trying to te the South, and should back off from meddling in the affairs of states.

Stephen Douglas held to the unpopular view of popular sovereignty concerning slavery in the various states. In other words, the people in each state should decide on whether slavery was to be allowed or not; and to if so, to what extent.

Abolitionists continually harangued the South that slavery was a sin, and that they were sinners. Southerners maintained that their cause was just, and that they were holding to the Constitution.

In hindsight, several conclusions can be reached: The South was wrong for wanting to expand slavery and maintaining that it wasn’t a sin. The North was wrong for continually pressing the issue and for virtually forcing the slave states to secede. The South shouldn’t have pressed for equal rights with the North. They were a minority region after 1850; they shouldn’t have tried to force the rest of the country to make allowances for them to have equal representation. The South was Presbyterian; the North was Unitarian. In that sense, the South was more Christian than the North, but the Southern Christians should have realized their sin and put a stop to it. (See my post on racism) The abolitionists should have waited for slavery to die out from natural causes and used the due process of the law to make slavery unprofitable; instead of forcing the South to do something it wasn’t ready to do yet. Stephen Douglas’ idea of popular sovereignty was probably the best idea in terms of slave vs. free states and the numbers of each. I don’t think it was good to have Congress decide the issue for the states. Both sides could have used a little more moderation and al lot less hot-headedness in their denouncements of each other.

All in all, the Civil War was not a shining moment in our history. It’s a little embarrassing. But nevertheless, it is part of our history, and we should learn from it.

No comments:

Post a Comment